- Home

- Viola Di Grado

Hollow Heart Page 2

Hollow Heart Read online

Page 2

The first to arrive was Gaia; she had a fashionable new asymmetrical haircut and a freshly ironed pink blouse. She did a lot of smiling. We sat down on the sofa together and she told me about a fight with Paolo, her boyfriend: they’d disagreed about the frames of his new glasses. Then Flavia got there. She brought me the birthday present that they’d been meaning to give me for the last six months: a shiny navy-blue-and-azure knee-length dress with a sixties harlequin pattern. I thanked them very much; I did a lot of smiling. We ate the paella, I tore every bite into little pieces with my teeth and sent it safe and sound down my esophagus. All the windows and even the door had been opened in an attempt to let in some air, but there wasn’t so much as a breeze, and every time someone climbed the apartment building’s stairs the enormous sound of footsteps reached us from the landing. Sitting there at the table, with the candle almost melted, each of us waited with bated breath for the stream of air from the fan to hit us.

“Dorotea?”

“What?”

“Why is this candle here, anyway? In the morning, with all this heat?”

“ . . . ”

“Dorotea, did you hear me?”

“Yes. Sorry, girls, I have a splitting headache.”

“Take an aspirin, do you have one? I might have some Tylenol in my bag, you want me to look?”

“No, no, thanks, I’m super tired too, I think I’ll just take a nap.”

“It’s still because of those pills, isn’t it? Why do you keep taking them?”

“No, they don’t have anything to do with it. I just want to get some sleep.”

They left, promising that we’d go to the movies the next day and see Paranormal Activity 3. Flavia’s boyfriend, Moreno, preferred going to the second show so he could study until late. I closed the door behind them. I turned on the TV; they were showing an American series with vampires or ghosts or young couples in love, it wasn’t clear yet. As I climbed the stairs to the second story of our apartment, canned laughter accompanied me: so it was supposed to be funny. What was it called? Who produced it, who conceived it? Who has laughed or wept or hated life while watching each episode? I would never know the answers to these questions. I’d never get any kind of answer at all, ever again. Before slipping into the chilly water I hung up the dress in my wardrobe. It would have gone perfectly with those light-blue ballet flats, the velvet ones with the bows.

It was 3:20 in the afternoon and my mother was at Aunt Clara’s, celebrating. Aunt Clara had just gotten a promotion at the textbook publisher where she worked; that’s why—as I slipped into the tub—crystal glasses were being raised on a terrace filled with carefully tended plants in Costa Saracena. I picked up the razor. I closed my eyes.

I thought of the ascomycete. That fungus whose spores land on an insect and then dig into it. The fungus grows inside it, slowly destroying the insect’s organs, until the insect becomes an empty sarcophagus. Finally, the mushroom erupts, enormous, disintegrating in an instant the body that by now belongs to it alone. It was a story Lorenzo had told me: at the time he was taking his doctorate in entomology. I listened with interest: at the time I was alive. We were sitting on the glider at Aunt Clara’s beach house, where we always spent hours and hours in the summer. We were wearing swimsuits; mine was a strawberry-colored bikini. The heat was atrocious, my mother was dressed in white, watering plants, and she seemed like a woman dressed in white watering plants. For the past few months she’d been doing much better than usual, and she would persist in that radiant normality until my death. On the balcony of the house next door a German shepherd was sleeping, wearing an orthopedic collar. My water-puckered fingers clutched the plastic razor, my eyes focused on the blue of my veins, I sliced my right wrist: error.

I tried again: error.

Nausea flooded my throat.

On the third try I felt a profound shock surge up from beneath the skin, sweeping through the entire organism, crying out for a full range of the body’s ambulances. The blood was warm. The blood wasn’t strange. I moved on to the left wrist. When the mushroom is about to split the insect open, the insect goes racing crazily up a tree, and then it suddenly shatters into pieces. The razor fell to the white tiles. Downstairs, on TV, there was a burst of canned laughter.

I still wonder why the insect starts running.

What is it trying to reach up there, at all costs? What is this thing, so strong and so punctual that every invaded insect feels it, always in the same instant, the moment before dying? Why did this thing not exist until just a second before, and why does it suddenly announce its existence in such an absolute manner? And who is it, inside the insect, that senses the arrival of the final moment? Is it the insect, what little remains of it, or is it the fungus?

I don’t know why I would be thinking of insects just before shuffling off.

If only they too—from the tiny flies to the Nicrophorus humator, terrifying stowaways in my corpse—would be still for a second and think of me in the pitch-darkness of my flesh, perhaps they’d rethink their destructive campaign and finally stop making me die.

2015

Four years have passed since my death.

The sky is still blue and people still live in houses. They hire gardeners to look after their yards and partners to look after their loneliness. They put moisturizing lotion on their skin and they put their hearts at rest. They watch movies on TV with Jennifer Aniston or Sandra Bullock, and they find them attractive. When spring comes, they put their overcoats in special cellophane bags and return them to their closets, they take advantage of the cafés with outdoor tables in the cathedral square to chat with their friends, and they inevitably gape in surprise at how the days have grown longer. Global warming and the hole in the ozone layer haven’t yet progressed from theory to outright apocalypse, and the cellophane garment bags for overcoats still say “an indispensable aid to ensure that your garments are safe from insects.”

My name is Dorotea Giglio and I’m full of flies. However much civilization might have trained you to be frightened of people like me, no one’s more scared than I am.

After my adolescence, there was a small chunk of adult life that I made exceedingly poor use of, followed immediately by livor mortis: two hours after my death I was red from head to toe. Then came rigor mortis, and by this point my eyes could be pulled open only from outside, like a doll’s. Then autolysis, or self-digestion. My cells self-destructed, one by one, until I was completely purified within: the final and ultimate examination of conscience.

Putrefaction was the most depressing part. That’s when the insects came along. The first-string squad, then the second-string, and the third: that’s what they call them, squads, and they always win, because I’m no longer an opponent, just a playing field. Last came the fourth-string squad. Like the others they went into me and they stayed a good long time: I am a first-class hotel, very discreet, and I cost nothing. Five months after passing away I was already popular: my skin filled up with black butterflies, whores with fast mouths and long outspread wings. They tore at my tissues as if they were so much wallpaper, until the terrible wall of my bones emerged.

And we’re not done yet.

Then Dermestes lardarius showed up, followed by the Nicrophorus humator. Slimy little vandals, with long dark legs that never seem to stand still. It’s their fault that my skin kept coming apart like party streamers, soft and red. What frightful festivities! All of nature was on the guest list. The cockroaches undid my ligaments, the Galasa cuprealis eagerly chowed down at the buffet table of my withered tendons. The beetles, unscrupulous tourists that they are, have been permanent guests in my arms—unbuttoned like antique gloves on my bare muscles—since 2012. Very soon, bleached clean of all signs of life, my skeleton will be as spotless and reassuring as sheets drying under the sunny skies of detergent commercials. Very soon, I’ll be gone.

Today is March 1, 2015.

Aboveground, spring has already arrived, but underground a black ooze is spreading, littered with dissolved scraps of my flesh and the rags of the sky-blue linen dress in which I was buried. In the Parco Falcone, surrounded by plane trees and palm trees and empty beer cans, the first petunias have bloomed. They burst out of the soil, without shyness, everywhere. At the foot of the red, orange, and blue jungle gym with the little metal slide. Under the empty benches. Under the chairs where old men play cards. Flowers spring up everywhere: the sun bestows its rays equitably upon them all; none are outsiders. There’s plenty of sunlight for all of them, and all of them will grow. My body, at the Catania city cemetery, tucked away where the sky can’t see it, dreams of that same growth and that same consideration on the part of the sun. It dreams of it the same way that it dreamed with me of becoming an astronaut when I was a little girl. It dreams of it but nature is Giuliana, the little elementary-school bully: even now that I’m a skeleton like all the other skeletons, I’m an outsider. Even now, with my empty eye sockets, the little fair-haired fifth-grade boy can still tell me I look like a whipped puppy. Even now, when all I have under my eyes is a jigsaw puzzle of deteriorating tissues, out on the playground the whole class still calls me “wicked witch” because of the circles under my eyes. Inside the coffin, I suffer as if there were still some remedy for my loneliness. As if my father might come back any minute now to tuck in what little skin remains to me.

In the meantime, the spring continues.

Daisies pop up over my dying body. To be exact, a good long way above it. There’s a considerable distance between us. The flowers live at an elevation I can no longer hope to attain: I’m no longer at their level, and there’s nothing I can do about it. Nature establishes a very rigid hierarchy. Now self-esteem is a matter of fertilizer: I no longer have any need for compliments and fulfilling relationships, nor do I care about achieving my goals. No matter what I do, the flowers will always stand head and shoulders above me.

People will see them and sometimes they’ll decide to pick them and take them home. As for me, there’s no longer any part of me that people can pick: they can’t even pick up on my witticisms and my ideas, since no one ever hears them anymore. The sun is friends with everyone, like a politician, but it can’t do anything for me now. My body is stretched out like a panhandler’s imploring hand: it begs for light or vitamin D, but it never gets anything at all.

In the Catania cemetery, a boxwood hedge—with its twisted trunk, its greenish bark—has taken root a few earthen floors above me and soon it will be closer to the sky, and to heaven, than I’ll ever be. My soul, in fact, never reached its destination, the afterlife that all religions count on. My soul stayed right here, like a foul residue stuck to the bottom of the pan. My soul is me.

It sounds saccharine or, even worse, New-Agey, but there’s nothing I can do about it, that’s my identity. It’s my identity, but really it’s closer to an atmospheric phenomenon of some sort.

Censored by my invisibility, I watch the others go on living. I recognize them, I understand them, I have plenty of words for them, but they can no longer see me. I’m invisible: the matter I’m made of is indecent, it demands secrecy. I’m invisible: I can no longer depress anyone with my depression, I can’t influence with my opinions, I can’t stir pity. I’m invisible: my body is taboo. I’m invisible, but it’s all a terrible misunderstanding.

Ladies and gentlemen, the sickness has passed: the heart has stopped, and with it all the other symptoms. Ladies and gentlemen, leave a contribution in flowers by my headstone corresponding to your grief. Now you can no longer use me or hurt me: now the worms are having their turn. You can’t tread on me either: the tree roots will reach me first. Ladies and gentlemen, don’t leave: my death, underground, goes on and on and on.

1986

My mother created me at age twenty-six, on a rainy day, in a dark kitchen with microwaves and pot holders shaped like animals. She had long legs and long lips and a husky voice. The kitchen belonged to a former classmate from college. And so did the sperm.

It was a mistake. It was a hole in the condom.

I don’t know what his name was and I don’t know what color hair he had. I don’t know what his eyes looked like or his favorite movies. I don’t know his shoe size or the words he used most frequently. I don’t know if he has a scuba-diving certification or a criminal record or one of those good-natured dogs with the smashed-in face that are so popular these days. I don’t know if he’s lost all his hair or if he’s lost all hope. I don’t know if he ever got married or what kind of work he does, whether he smokes, if he plays computer games, if he likes spicy food, if he has an electric toothbrush, a pink shirt in his dresser drawer that he never wears, a picture of someone in his wallet, or a subscription to a magazine he doesn’t read. I don’t know if he has holes in his socks, a sweet tooth, a gift for telling jokes, whether he wakes up early, drinks coffee, whether he laughs with his mouth shut or open so wide that you can see his gums, I don’t know what he wears around the house or what he reads at night before falling asleep, I don’t know whether he reads and I don’t even know if he sleeps, I don’t know whether he talks a little or a lot, I don’t even know if he talks at all, I don’t know if he’s mute, I don’t know if he’s alive. I don’t know any of these things and I almost never want to know them.

They weren’t even dating; they didn’t know each other’s last names. They just met at a party at the house of a mutual acquaintance, they’d talked about school and about what they were doing: he still wasn’t doing anything at all. Then back to his place, that same night. And in the weeks that followed, a couple of movies and a drink at a bar in Piazza Teatro Massimo. Then that was it. After he got the news, a month later, she never heard from him again. But she swore to me that he came to celebrate my third birthday, that he was there, he was there. Then gone forever.

This is all I know and I often tell myself that it’s all I need to know, and I almost always believe it. My mother never told me anything else about him, except that she certainly didn’t need some asshole at her side to raise me. She never answered my questions about him, and before long I started keeping those questions to myself. After a while I had fewer and fewer of them. They withered from lack of sunlight.

My mother had lips as long as asps and her name was Greta; I got to know her with the masks of her camera lenses between us. After my birth she rented an apartment with a cellar storage area. She immediately turned the little cellar space into a darkroom, and the rest of the apartment into a dark apartment. We used electricity only sparingly because we had so little money, and we used our faces to smile only sparingly because happiness wasn’t something we did well.

I was born by natural childbirth in a bathtub and I died of unnatural death in the same place. I grew up surrounded by old furniture that reeked of stale wood, the furniture of grandparents I’d never seen. In the living room there was a large mirror with gilt edges, and the reflections in it were opaque and deformed, gray and split in half by a crack. Whenever I looked at myself I’d decide to be either the one on the right or, other times, the one on the left. The windows were always open and the curtains twisted and tangled, the parquet floor was covered with crushed dry leaves that came rustling in from the outside world and didn’t know how to get back out to it.

Four beechwood chairs in the dining room: two empty ones next to the table, the other two relegated to the corners. On the chair in the left-hand corner sat a mangy teddy bear missing its right eye that had belonged to Lidia when she was a girl. On the chair in the opposite corner was the empty cage that once held two hamsters I’d been given for my fifth birthday, but after a week the boy hamster had gnawed the girl hamster’s legs off: we didn’t find her mutilated body until she was dead, and my mother threw the killer hamster into the toilet as a punishment, but he kept coming back up, bug-eyed, so she’d had to flush five times. A dining room table in black walnut, and on it

camera lenses and empty cigarette packs and a black-and-white photograph torn into pieces so small that it was impossible to say what they depicted. Overhead, a fifties crystal chandelier, solid and drab as a dog’s teeth, and all around it long gums of dampness spreading out across the whole ceiling. Very little daylight came in, and when it did it soon regretted it. Like a moth, it wanted to return outside but didn’t know how. Like a moth, it ran blindly into things, misunderstood them, feared them.

And dust everywhere. Between the doorjambs. Even on the lacquered side table by the front door, around the broken wing of the small porcelain phoenix that Aunt Clara brought back from her first honeymoon in China. Dust engulfing the legs of the chairs in the dining room, both the empty ones and the ones in the corner. Dust on the raised arm of the teddy bear and in the unstitched hole where his missing eye had once been.

Even the television was covered with dust. And if you moved a piece of furniture you were blinded by a toxic cloud of fine gray grit. Thick, grainy dust. An entire fortress of dust under my bed, even inside the shoebox where I kept my diary. Dust on my shelves between one book and the next. Dust that went on to spawn more dust, and that in my death fermented, expanded, monstrified. Dust that developed legs and arms, strings of gray muscle that now extend over my bed and my windowsill, filling the red mug full of pens, and the crack between my bathroom door and the wall. They even fill your eyes if you look at any object close up. They cling to your fingertips if you touch the green alarm clock, the nightstand, the locked armoire, or the sink, or the bathtub. Now the sofa in front of the TV is wrapped in a clear plastic slipcover and on it the dust rests peacefully, like the remains of a tattered beast. Indestructible dust, fairy dust, from dust we are born and to dust we shall return.

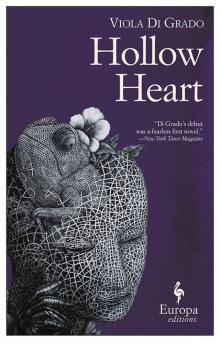

Hollow Heart

Hollow Heart